A few weeks ago, I went to Varanasi on a pilgrimage. Not to a temple, but to Lamhi, the birthplace of Hindi literature’s greatest writer, Munshi Premchand (1880-1936).

Lamhi is a few kilometres north of Varanasi. It was a tiny village when Premchand was born. His grandfather, Gursahay Lal, moved there as the patwari or land recorder, built a mud house and settled in. Gursahay Lal’s son, Ajaib Lal, found work as a postal clerk. Premchand, born after three girls (of whom only one survived), was a mischievous child, given to stealing sugarcane and mangoes from fields and orchards, leaving the owners very cross. But what he truly loved, and was excellent at, was gilli danda.

In this way, his childhood was spent, until it fractured.

When he was eight, his mother Anandi Devi died, casting a long, deep and sorrowful shadow over his life. His stories and novels are full of characters whose mothers die when they are seven or eight years old. His father married again, but the little boy never got the love he craved from his stepmother. By the time he was 17, his father had died too.

In the course of his life, Premchand lived in different parts of present-day Uttar Pradesh, first as a student, then in his transferable job as a school teacher and school inspector, and later (after he had resigned from the job) because of various literary and journalistic assignments. He lived in Gorakhpur, Banaras, Bahraich, Pratapgarh, Allahabad, Kanpur, Basti, Lucknow.

But in the summer, he always returned to Lamhi.

His stepmother was, by all accounts, an indifferent housekeeper. He wrote, in a letter to a friend, that he sometimes struggled to find a room worth sleeping in, and ended up making a makeshift bed in the cubbyhole where grain was stored. (In later years, he renovated the house, making it more habitable.)

Much of his deep understanding of village life came from his decades of returning to Lamhi.

In 1934, aged 54, Premchand’s famously travelled to Bombay to write plots for the film company Ajanta Cinetone. He hated it. He said no one cared much for Hindi in that city, and few really cared for storytelling. Within 10 months, he had left and returned to Lamhi, where he set about finishing what would be his last novel, the magnum opus Godan.

With all this a half-hour drive away from Varanasi, I knew I had to visit Lamhi. I had heard there was finally a museum of sorts too, set up there in the writer’s memory.

I cannot express my disappointment when I got to Lamhi. A faded sign at the entrance to a small compound declared that this was the Munshi Premchand Smarak. A garlanded bust of the writer stood under a metal roof. To the side was a single-room structure with a verandah outside it. The room held a few bookshelves bearing copies of his books.

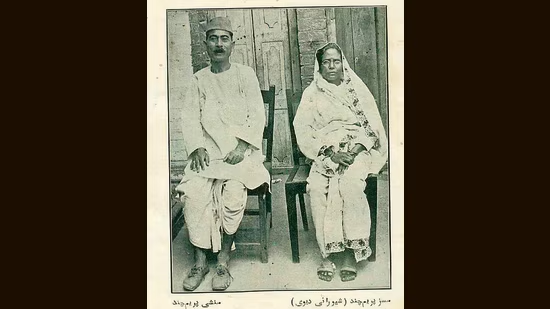

On the walls of the verandah were hazy pictures, including the famous one of the writer with his wife Shivrani Devi, titled Premchand ke Phate Joote, in which he can be seen wearing torn shoes. (The photograph would inspire the great satirist Harishankar Parsai to write an essay of that title in the 1960s, about poverty, dignity, neglect, and intellectual greatness.)

Back at the “museum”, on one wall hung a gilli danda with a handwritten note saying: Premchand ka priya khel (Premchand’s favourite sport). Also affixed to a wall was a chimta (pair of tongs), in a salute to his classic story Idgah, in which five-year-old Hamid uses his Id gift money to buy a pair of tongs for his grandmother instead of a toy for himself, because he has noticed that she singes her fingers when she makes chapatis for the family.

That was more or less the extent of the memorial.

The best thing about it turned out to be its caretaker, Suresh Chandra Dubey, a walking encyclopaedia on Premchand. He told us stories of his life and his work, with accuracy and affection.

I had very much hoped to see a simple, elegant memorial befitting a great writer. Perhaps some artefacts to help tell the story of his life, and a neatly organised little bookstore, with some merchandise such as postcards and posters.

Standing in that barren lot, it hurt to think of the many beautiful memorials dedicated to authors around the world.

Here, it is left to dedicated individuals such as Suresh Chandra Dubey to try to make up, with genuine passion, for years of neglect and apathy.

(To reach Poonam Saxena with feedback, email poonamsaxena3555@gmail.com. The views expressed are personal)